A stone’s throw from Nigeria’s vibrant, congested and often chaotic capital Lagos, a grandiose new smart city is in the making – rising on land reclaimed from the Atlantic Ocean. Eko Atlantic envisions itself as Africa’s cutting-edge economic capital, a self-sufficient and sustainable city right next to the continent’s most populous city.

Construction on the 300 000-resident project has been ongoing for nearly a decade. The privately funded city will generate its own power (partly through solar panels), use treated effluent for irrigation and provide fibre optic communications to every plot of land.

In south-eastern Mauritius, another ‘smart’ coastal development is attracting investors. Mon Trésor is the first of eight smart cities under the island nation’s Smart City Scheme, in which the government has set aside tax incentives for local and foreign investors. The project promotes the ‘live, work, play’ concept and is marketed around principles of sustainability and seamless connectivity that ‘reconciles urban intelligence with nature; technological innovation and eco-responsibility’.

In Kenya, yet another greenfield project is transforming into a new African smart city. Located 60 km south of Nairobi, Konza Technopolis intends to become a world-class tech and innovation hub. The project has been nicknamed ‘Silicon Savannah’ and is expected to cost US$14.5 billion, which according to Ventureburn will be primarily funded by the private sector, with the Kenyan government contributing about 10%.

Konza will be a walkable, sustainable green city that comprises a science park with various tech businesses, a university campus specialising in research and technology as well as schools, health facilities, hotels, shopping malls and a residential area.

The Konza Technopolis Development Authority says that data will be gathered from smart devices and sensors embedded in the urban environment, such as roadways, buildings and other assets. The agency website explains: ‘Collected data will be shared via a smart communications system and be analysed by software that delivers valuable information and digitally enhanced services to Konza’s population. For example, roadway sensors will be able to monitor pedestrian and automobile traffic, and adjust traffic light timing accordingly to optimise traffic flows.’

Residents will have access to the collected data, which may be used for traffic maps, emergency warnings, and detailed information on energy and water consumption.

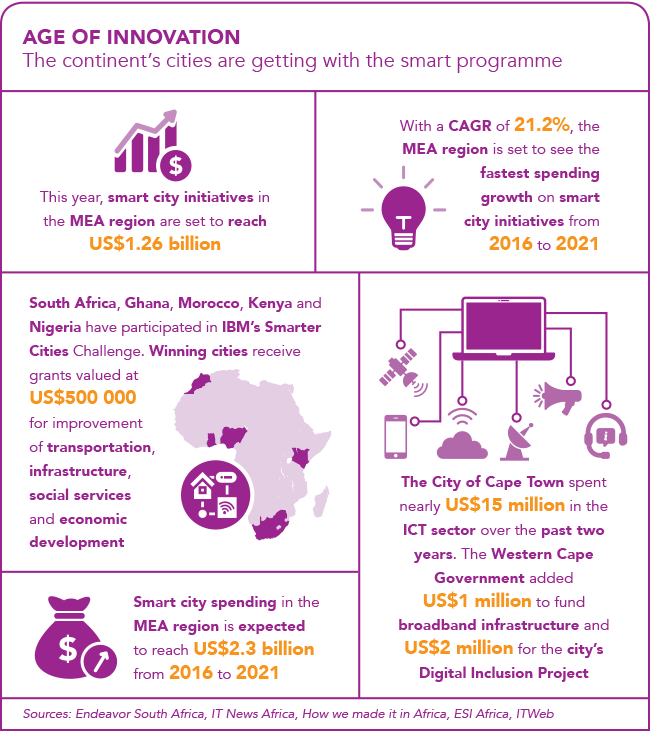

While the completion of Konza Technopolis will take some time, other African cities have started to implement smart city frameworks. In 2017, Rwanda presented a Smart Cities Blueprint for Africa, which urges African nations to adopt ICT-driven strategies for smarter cities while also giving guidance on how to establish – and finance – such developments.

There are various definitions of what makes a city ‘smart’, but essentially it involves using technology and data analysis to improve a city’s functions and the quality of life for all its citizens – whether they live in informal settlements or upmarket suburbs. Advances in automation, the internet of things (IoT) and AI are all contributing to the adoption rate.

The use of IoT, for instance, enables a municipality to gather real-time data from millions of objects, such as water and electricity meters, waste bins, traffic lights and street lights. In water management, IoT (especially when coupled with AI) can be useful in the early detection and management of malfunctions, making it possible to adjust water pressure and flow rate, as well as remotely close valves or redirect water in the case of a leak or burst pipe.

‘Artificial intelligence and machine learning continuously apply insight from data within these systems – and even across closely related systems – delivering a holistic and systems-based approach to water management and conservation,’ states SqwidNet, which is a subsidiary of Dark Fibre Africa, a provider of open-access fibre connectivity.

Since being launched in November 2016, SqwidNet has successfully deployed a low-cost, low-power, ultra-narrowband IoT network that covers eight metros and more than 85% of the South African population. ‘Our technology allows for ordinary citizens to have real-time visibility into how they consume shared resources,’ says Phathizwe Malinga, acting CEO of SqwidNet. ‘For example, knowing how much water you use via our water meter readers, allows you to comply to the daily quota set better if you live in Cape Town.

‘Another practical example is Kalafong Heights in Pretoria, where residents are able to track the real-time quality of the air on a website, as it could be affected by the recycling facility in close proximity. This information has helped the facility combat bad odours as they arise, which we believe will reduce potential health issues.’

In order to access such online services, citizens require free public WiFi – particularly in Africa, where the majority of people struggle to afford costly mobile data. While the number of free WiFi hotspots is increasing in urban areas across the continent, there’s still much room for improvement.

In South Africa, the national broadband project SA Connect strives to provide 100% WiFi connectivity to government facilities by 2020. This is vital for the roll-out of e-government services that allow citizens to digitally engage with their local government, as already implemented in Cape Town, Ekurhuleni, Buffalo City, Knysna and George.

In July, the City of Johannesburg launched an integrated ICT system to simplify its ‘cumbersome’ municipal operations. In partnership with SAP, EOH, Gijima and Accenture, the city will automate its business processes and create a single view of municipal services. The open portal will enable city residents and employees to view their personal profiles, manage their energy consumption, pay municipal bills and apply for leave.

The new system will digitise the waste management service Pikitup and the Johannesburg Social Housing Company, as well as integrate the billing between City Power and Joburg Water. Furthermore, the city will be able to monitor and manage the municipal fleet, including the bus rapid transport and metro buses, and manage inner-city traffic congestion. City manager Ndivhoni-swani Lukhwareni said in a statement that this would not only cut costs but also revolutionise municipal operations. ‘This implies a conscious effort to use ICT to transform the general quality of life for residents,’ he added.

Across the continent, smart city technology is improving the quality of lives – as in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, where Africa’s first automated car parking system was recently introduced to save space and ease traffic congestion. Worldwide there’s no shortage of innovative ideas: in Barcelona, Spain, smart rubbish bins have been equipped with IoT sensors to optimise the routes of refuse collection vehicles. This will save 10% in waste disposal costs, according to the Gordon Institute of Business Science.

Its report Smart Cities and Smart Grids highlights the following applications: intelligent streetlights in Amsterdam, Netherlands and Glasgow, Scotland (where streetlights automatically turn on and off for greater energy efficiency); autonomous vehicles and traffic flow management in Singapore (where sensors used for electronic road pricing and sensors attached to taxis help the mapping of traffic conditions); city-wide sensing in Santander, Spain (in this worldwide largest city-wide sensing pilot, 12 000 IoT sensors collect data on everything from parking space availability to air quality); and energy management solutions for smart buildings in Canary Wharf, London, UK (where sensors are used to monitor energy use and manage waste).

While Africa can learn from these first-world examples, it’s important to note that smart city solutions depend on the unique context of a particular city.

‘Smart cities are generally thought of as technology marvels that are totally connected and integrated,’ says Alison Groves, regional director, WSP, Building Services, Africa. ‘I believe that in the African context, and knowing the challenges faced in African cities with infrastructure deficit to support the population growth we are seeing, we need to take a different approach.’

She argues: ‘There needs to be more focus on infrastructure development that will support sustainable cities that are totally integrated – and cities that are “people” focused. This will mean reviewing all current infrastructure plans and projects to understand what is the socioeconomic and environmental impact of these.’

The leading African cities understand the complexity of what it means to become an inclusive smart city. As the examples show, they are at different stages of their journey, with some innovative solutions already taking place.

Meanwhile, the continent’s smart cities in-the-making, such as Eko Atlantic, Mon Trésor and Konza, have the luxury of getting it right from the start. They may become high-end global showcases for a people-centric, technologically connected and sustainable urban future.