The Single African Air Transport Market (SAATM), or so-called ‘Open Skies’ policy, was launched in January 2018 by the AU at its 30th summit, held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. By end-September 2018, 26 of Africa’s 54 countries had signed the agreement. While continent-wide agreement with Open Skies seems slow in coming, consensus in the industry appears to be that once all the countries sign it and it comes into effect, it will create plentiful opportunities for tourism, business and trade. Indeed, both the AU and the International Air Transport Association (IATA) have said that to make the air travel industry profitable, African countries need to liberalise air traffic.

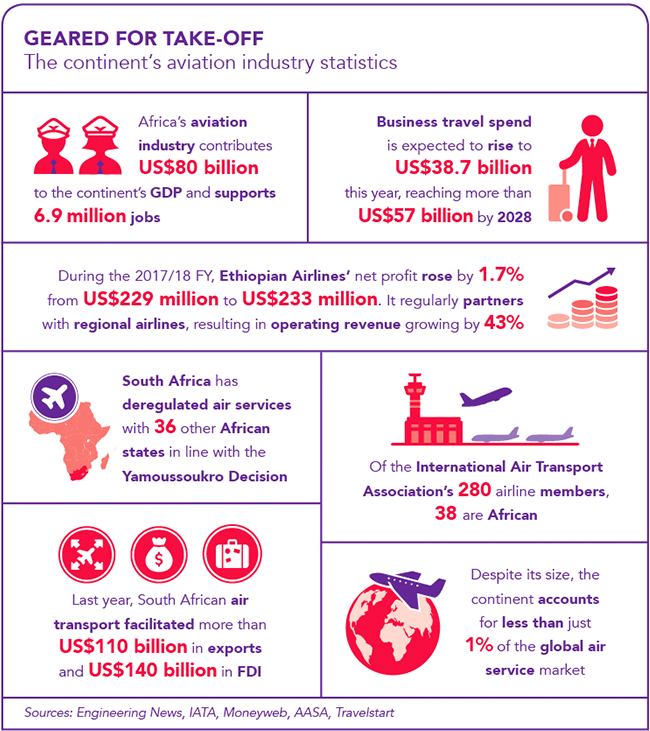

‘Africa is one of the fastest-growing aviation markets in the world and this is set to continue with initiatives like Open Skies,’ said Michael Gill, executive director of the Air Transport Action Group, during his keynote address at the Board of Airlines Representatives of South Africa Aviation Summit earlier this year. He added that, globally, the aviation industry employs more than 60 million people and contributes 3.5% to world GDP annually, In Africa, around 7 million people work in the sector, which generates US$70 billion for the continent’s GDP. That said, studies show that fewer than 10% of the 1.2 billion population use air transportation.

Raphael Kuuchi, IATA’s vice-president for Africa, believes the Open Skies agreement represents a decisive move towards greater intra-African connectivity. However, he cautions, the continent will only realise the full benefits if more countries commit to the agreement and if it is efficiently implemented. He says that every open-air service agreement implemented in the world to date has boosted traffic, lifted economies and created jobs. ‘And we expect no less from Africa on the back of the SAATM agreement.’ He adds that the benefits of a connected continent will only be realised through effective implementation of SAATM by the countries already committed and by the remaining AU countries still to come on board.

Corne de Waal, CEO of RMexpertise, notes that while Africa is the second-largest and second-most populated continent on Earth, it accounts for around just 3% of the world’s air traffic. ‘This SAATM should lead to an increase in intra-Africa flights, which will enhance air connectivity, stimulate employment and aid economies in general,’ he says. ‘African carriers and passengers have been burdened by high fares, low air-traffic growth, old aircraft with poor safety records and very limited choice of flights. The implementation of a SAATM is the ideal breeding ground for the establishment of low-cost airlines, which will address the current shortcomings.’

Unisa professors Petrus Potgieter from the department of decision sciences and Ciná van Zyl from the department of entrepreneurship, supply chain, transport, tourism and logistics management, agree. ‘Open skies agreements always result in a general increase of the size of the aviation market and a general fall in prices for consumers because of enhanced competition. So a single market is definitely good for the industry as a whole. Specific operators, however, could easily find themselves crowded out of the market by more efficient new entrants or operators from another country in a liberalised market.’

Stephan Krygsman, associate professor in the logistics department at Stellenbosch University, believes it is important to emphasise that opening up a market tends to deliver ‘winners and losers’. He says: ‘Generally the winners will be those with the lowest cost structure and highest productivity, and this would ultimately be reflected in lower flight costs for travellers. But of course this is a big “if”.’

He also believes that the opening up of the market may result in the emergence of a host of secondary airports. ‘I think you will start seeing the emergence of hub-and-spoke systems on the sub-continent,’ he says.

Paul van den Brink, Cape Town Air Access project manager, says that Africa’s skies are currently tightly regulated, protecting carriers in their home markets. ‘Open Skies will change the aviation model with opportunities for regional and long-haul low-cost carriers, making travelling within Africa easier and more affordable,’ he says. ‘Over the past three years, African accessibility to and from Cape Town showed impressive growth, with four African airlines – Angola’s TAAG, Ethiopian Airlines, Kenya Airways and RwandAir – commencing operations, with eight destinations added to the network. Cape Town Air Access expects the SAATM will make it easier for Cape Town to create connectivity with West Africa and North Africa, which will assist in boosting business and tourism with these parts of the continent.’

There are several, perhaps obvious, benefits that will come from the implementation of the Open Skies agreement. Certainly one of the most important of these will be a positive impact on tourism, as it will be easier for leisure travellers to connect via the major hubs to countries that are currently difficult to access. Business travellers, meanwhile, should benefit from improved connections, which will shorten their overall travel time. In addition, flights within the continent are currently relatively expensive – compared to flights within countries or to other continents – and many travellers connect through Europe or the Persian Gulf to fly between African cities.

Asked whether he thinks opening up the markets will stimulate business and personal travel, Krygsman says that’s ‘very much a function of whether the other requirements are in place’. He cites an acceptable business climate and holiday destinations as two examples of such requirements. ‘But it definitely does provide the foundation for more interaction between African nations, which can lead to increased trade and ultimately support economic development,’ he says. ‘You will also find that opening up markets has implications beyond the airline industry. It allows clients to access larger markets and source products and services from a wider market, thus lowering costs.’ He cautions, however, that all of this will only be possible if the institutional systems, such as communications and documentation, for example, are also in place. ‘This is something that is long overdue in Southern Africa,’ he says.

While most have welcomed the Open Skies agreement, some (such as Airline Operators of Nigeria CEO Noggie Meggasin) have called it ‘putting the cart before the horse’, arguing that there are other important issues that must be addressed first. De Waal says that for all countries to benefit, it is important that the playing field is somewhat level, or at least not hugely uneven. ‘Nigeria is a good example. The private airlines in Nigeria will have to compete with major alliance airlines and have very little chance in succeeding. The biggest challenges that plenty of local African airlines face are funding, expertise, economies of scale/partnerships and access to information,’ he says. ‘Without these, they will never stand a chance against the big carriers. I believe this needs to be addressed to give everyone a fair slice of this very lucrative cake.’ His proffered solution is that some regions form partnerships and create a regional airline. ‘This way the individual burden on each country is less to obtain the necessary resources to effectively and safely compete,’ he says.

Potgieter and Van Zyl express concern over the slow speed at which the agreement might be implemented and what the ramifications of this delay might be. ‘The agreement is based on the Yamoussoukro Decision of 1999, itself based on a declaration from the 1980s, which should indicate the speed one can expect on the journey towards a single aviation market. Delays in this will, however, allow the share of intra-African traffic going via the Persian Gulf or Europe to increase further to the extent that there might be few viable African airlines left to avail themselves of the single market when it arrives.’

The pair further state that, while it is a good idea to proceed with liberalisation under any circumstances, there must be a commitment from governments and civil society to implement the agreement efficiently and quickly. They add another caveat: that the operation of airports is highly relevant to the success of this agreement but that the right to fly (even if and when a single market is achieved) does not guarantee the availability of landing slots at airports. ‘Johannesburg, for example, has two international airports operated by different companies, so it will not be so much of a problem in South Africa’s main business centre,’ they state. ‘In Windhoek or Yamoussoukro, however, the situation could be different.’