Remember that clunky old phone you ditched last year when you got an upgrade? Or that fried PC monitor that had to be tossed? No harm done, you might think. But these unloved gadgets represent one of the major environmental hazards of our time.

Electronic or e-waste, also called WEEE (waste electrical and electronic equipment), consists of all the discarded electrical devices that power our modern lifestyle – from fridges to mobile phones and batteries. With rapid tech advances, lower costs and shorter device lifespans as we continually replace them with newer models, the sheer mass of dead gadgets piling up in landfills is becoming overwhelming.

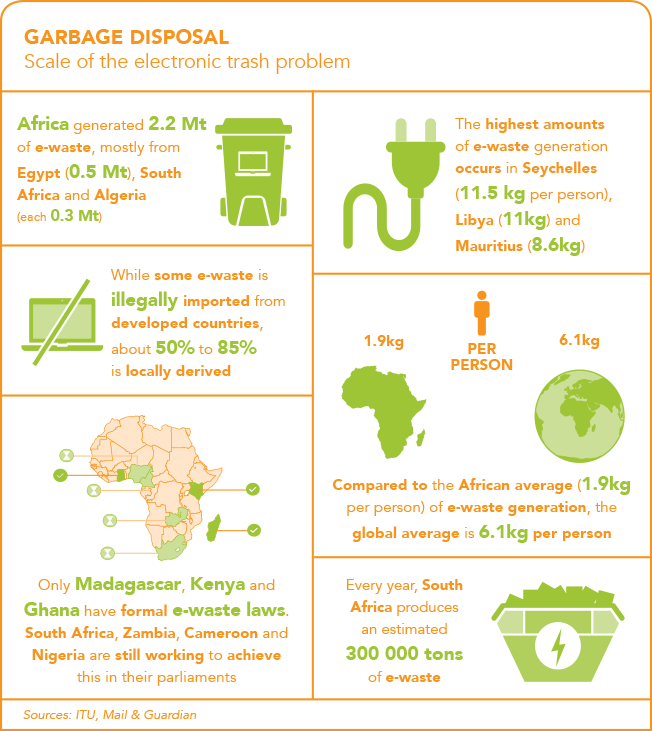

It’s estimated that globally, the electronics industry currently generates up to 50 million tons of e-waste a year, with mobile phones being a major culprit. As consumer numbers increase and technology accelerates, these figures can only rise. In Africa, as elsewhere in the world, this is a huge problem. South Africa is the leading polluter on the continent, producing more than 300 000 tons of e-waste annually – and counting. In fact, this waste stream is growing faster than any other. Even if you stash your old gadgets in the back of a cupboard and not in the trash, it still represents a damaging waste of energy, resources and, not least, business opportunities. For one thing, electronic goods contain valuable minerals such as copper, gold, beryllium, tantalum and coltan. These could be productively recycled, saving energy and the non-renewable resources depleted in mining.

More frighteningly still, e-waste also contains a complex array of chemical substances, many of them toxic – lead, mercury, cadmium and many others. According to the website of the e-Waste Association of South Africa (eWASA), ‘a typical computer monitor may contain more than 6% lead by weight’. In addition, it states that up to 36 separate chemical elements are incorporated into e-waste items. ‘It presents difficulties for recycling due to the complexity of each item.’ For example, many plastics used in electronic equipment contain flame retardants, which make them difficult to recycle. If these toxins find their way into landfill sites, they can contaminate groundwater, leach into the soil and, if burnt in an uncontrolled manner, pollute the air. The result? Major damage to the environment and a health risk for the wildlife and human beings that are exposed.

Hardest hit, often, are the informal collectors, dismantlers and recyclers – the main actors in the processing of e-waste in Africa. Such people often work under extremely harsh and exploitative conditions that are very difficult to monitor. ‘Stories abound of the horrendous working conditions in different parts of Africa where imported waste goes to die,’ says Muna Lakhani, volunteer branch co-ordinator of South African environmental NPO Earthlife Africa and national co-ordinator of the Institute for Zero Waste in Africa.

Often, these dangers are imported from more affluent parts of the world: despite international conventions aimed at reducing this problematic trade, illegal cross-boundary movement of waste within and into Africa persists, usually run by criminal gangs. West Africa is a major destination for e-waste, according to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime. Globally, the bulk of such waste – anything from 60% to 90% of the total – is illegally traded or dumped, according to UN Environment Programme (UNEP) research. Collectively, these rackets are worth nearly US$19 billion. ‘Under the guise of “recycling”, highly toxic waste is being dumped on poor communities,’ says Lakhani.

What seems an intractable problem, however, is also an opening for entrepreneurs. Recycling e-goods can cut down on pollutants in the environment and be a source of income, ‘green jobs’ and valuable secondary raw material.

According to eWASA chairman Keith Anderson, there is an enormous opportunity for e-waste recycling in South Africa and Africa. ‘eWASA, through its members, has about 1 000 collection points. However, we need at least four times more collection/dismantling facilities.’

A 2017 market intelligence report by GreenCape (a South African NPO promoting green economy solutions) points to the rapid growth of this sector. In 2009, there were just two large e-waste recyclers in South Africa (Universal Recycling Company and Desco), dismantling and processing 9 000 tons annually; by 2016, there were more than 20, processing 45 000 tons.

The report continues: ‘The barriers to establishing an e-waste dismantling business are lower than that of dry recyclables, with a higher job factor (30 created for every 1 000 tons diverted) … This is a sector that can generate significant growth, as an 8% increase in e-waste diversion can result in a market potential of ZAR22 million and create 650 local jobs.’

The potential for employment creation and small business growth is therefore huge – and currently, African countries are not taking full advantage. South Africa, for example, only recycles 6% to 10% of its e-waste, with most of it exported or going to landfills, according to Anderson. At least 90% of printed circuit boards and 80% of plastic recovered from South African e-waste is exported for processing, according to a 2014 study conducted by Mintek, the Department of Science and Technology and the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) – thus losing economic benefits to the country. ‘If we can unlock this uncollected e-waste into the local value chain, we can create opportunities to grow South Africa’s e-waste recycling economy, as well as opportunities to increase investment in appropriate technologies and in innovative new technologies,’ says Linda Godfrey, manager of the CSIR’s waste roadmap implementation unit.

Individual consumers can combat e-waste by making sure their obsolete electronics are disposed of at accredited e-waste facilities, where products are properly wiped of data, dismantled, sorted and prepared for recycling. Several electronics and computer dealerships provide convenient drop-off bins where you can dump your old devices.

In South Africa, many e-waste facilities belong to eWASA, established in 2008 to manage the establishment of a sustainable, green, national e-waste-management system, working with manufacturers, vendors, distributors, waste handlers and other players. eWASA has also recently established the WEEE Africa Forum, which aims to create a uniform standard of responsible e-waste treatment across Africa – ‘from Cape to Cairo’, as Anderson puts it.

Significant power for change lies in the hands of the corporations that make electronic goods. Some companies have taken the initiative, with programmes in place to take responsibility for the entire life cycle of the product. Samsung, for example, ‘aims to minimise its products’ environmental impact by maximising resource efficiency from assembly to eventual disposal’, according to Justin Hume, MD of Samsung South Africa. ‘This entails reusing parts … and increasing the recyclability of new products’ components for later use,’ he says.

Samsung has also reduced its use of hazardous substances over the past few years – their latest TVs and smartphones are free of certain commonly used, potentially harmful substances, including PVC plastic, some flame retardants and phthalates.

Governments also have a role to play, in regulation and oversight of waste disposal. The South African government, for example, has had e-waste on its radar for some time – from the National Environmental Management Act of 1998 to the Waste Act of 2008. However, industry uptake has been spotty – adherence by companies has been voluntary and not well monitored.

However, this may soon change. In December 2017, Environmental Affairs Minister Edna Molewa issued a Section 28 notice calling for industry waste-management plans (IWMPs) to be submitted by September 2018. With this, responsible industry treatment of e-waste should become mandatory. The emphasis is on waste reduction, followed by re-use, recycling and composting, then recovery to create energy – and disposal as a last resort – according to the IWMP guidelines on the Department of Environmental Affairs website.

This is only the start of the battle. Anderson points out that government should only have oversight of the process. Industry needs to have the task of overhauling itself, along with organisations such as eWASA that can ensure independence and transparency. ‘Once we have a legal framework in place, we need to build capacity and have a set of compliance standards. This will level the playing field and in turn create jobs. We will need to establish more certified dismantling and treatment facilities. Public awareness, education and training need to be escalated.’

Lakhani goes further, calling for ‘wholesale redesign’ – products that can be disassembled for repair and upgrade should be the norm; materials used should be easily re-integrated into new product lines; and product take-backs should be routine. ‘Much of this requires both policy interventions, but also – equally important – a stern and punitive backlash upon non-performing companies. Nothing changes otherwise.’