In Kigali, Rwanda, on 21 March 2018, government leaders launched the most ambitious continental economic initiative to date, the African Continental Free Trade Agreement – the AfCFTA.

It’s is an undertaking to drop almost all tariff barriers in goods and services and also eliminate many non-tariff barriers right across the continent. Of the AU’s 55 member states, 43 signed the declaration, committing them-selves in principle to joining the AfCFTA, and 44 signed the agreement establishing the AfCFTA.

Its scope is huge. It would, if successful, create a gigantic market of 1.07 billion people and US$3.3 trillion, taking the continent a giant step towards its long-held dream of an African Economic Community.

E-commerce, intellectual property and competition policy as well as trade facilitation measures – such as the elimination of cumber-some red tape at border posts; long delays in ports and roadblocks; and boosting trade-related infrastructure – also fall within the AfCFTA’s ambit. The potential benefits for the continent are enormous. ‘The Continental Free Trade area will stimulate intra-African trade by up to US$35 billion per year, creating a 52% increase in trade by 2022; and a vital US$10 billion decrease in imports from outside Africa,’ AfDB president Akinwumi Adesina said at the launch. Economists have also calculated that the AfCFTA could boost GDP by up to 6% and expand Africa’s industrial exports within the continent by more than half, also by 2022.

Stephen Karingi and Simon Mevel, economists at the UN Economic Commission for Africa, estimate that the AfCFTA would increase the continent’s real income especially for unskilled workers in non-agricultural sectors. They also forecast that the trade boost would be highest in industry – of the US$34.6 billion increase in intra-African trade produced by the AfCFTA by 2022, US$27.9 billion would be in industry, US$5.7 billion in agriculture and food, and US$1 billion in services.

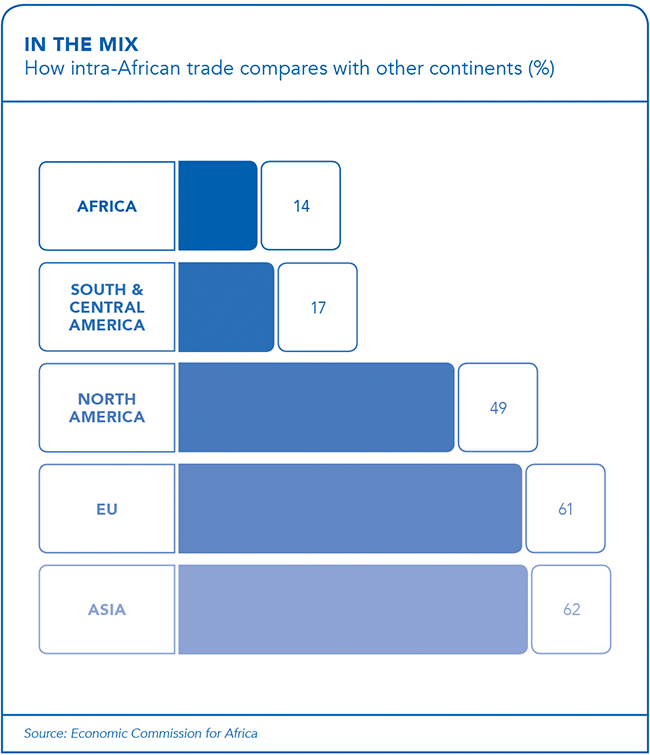

These figures indicate that the AfCFTA could improve the sophistication of African economies by boosting manufacturing and so adding value to trade within the continent, as opposed to the unprocessed raw materials that now dominate Africa’s exports to the rest of the world. Overall, the AfCFTA could increase the share of intra-African trade from just 10.2% in 2010 to 15.5 % in 2022.

An AfCFTA that includes the extensive envisaged trade facilitation measures – such as more efficient customs procedures and reductions in delays of goods in African ports – would also boost intra-Africa trade by a very substantial 128.4% (or US$85 billion) by the year 2022, compared to 52% without the trade-facilitation measures. That would also more than double the share of intra-Africa trade from 10.2% in 2010 to 21.9% in 2022.

The Kigali signing ceremony did not bring the AfCFTA into force. It was a largely symbolic event, conceived by Africa’s prime mover (and shaker), Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame, to jump-start the AfCFTA into life. And the AU and its member states, not usually known for great expedition, seem to be moving with unusual speed to do that.

Earlier this month, AU trade ministers and officials meeting in Dakar, Senegal, came close to finalising the AfCFTA’s protocols on goods and on rules for settling disputes. They also agreed on the five priority sectors for the agreement – transport, communication, financial services, tourism and business services – and on the approach towards adopting commitments on trade in services.

They decided that at their next meeting, probably in September, they would approve the templates for AfCFTA operations. After final adoption by the January 2019 AU summit, the AfCFTA should be ready to go live. Even though that was originally supposed to happen in 2017, it would still be remarkable.Is it, however, credible? Or is it simply another example of Africa’s propensity for thinking big and doing small?

The Trade Law Centre (Tralac) at Stellenbosch University in South Africa – observed: ‘The record regarding intra-African trade and the settlement of trade disputes is not impressive. Integrating unequal partners is difficult. Some are concerned about the loss of tariff revenue, and have limited options for expanding their domestic tax base.’

Former AfDB president Donald Kaberuka, now AU high representative for financing of the Union and Peace Fund, acknowledged concerns about the AfCFTA, including the scepticism about implementation, at a discussion at the Wilson Centre in Washington in May. According to him, getting the AU to implement its decisions is ‘the whole essence’ of the wider AU reforms that Kagame, the current AU chairperson, is leading and which have been adopted by the continent’s leaders. Kagame’s first proposal ‘is precisely to deal with the implementation crisis – decisions taken and not implemented’.

Kaberuka added that establishing the AfCFTA was ‘an existential issue for the AU’ as the continent would ‘go over a demographic cliff’ caused by a population explosion, unless it took decisive action to boost growth and thereby create jobs for its restless, booming youth population. He also addressed the misgivings of the many African states that have little or weak manufacturing capacity that they will be simply swamped by the continent’s bigger and better economies, giving the reassurance that the AfCFTA would cover about just 90% of trade, allowing states to protect sensitive or infant industries. He also said the agreement would put a lot of emphasis on services, so countries with little or no manufacturing bases would not be left out of the picture.

The fear of competition is not only felt by small states – neither of the continent’s two largest economies, South Africa and Nigeria, signed the AfCFTA in Kigali (although South Africa has since done so). Yet while Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari called off his visit to Kigali, South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa attended and signed the AfCFTA declaration.

He explained then that, by law, South Africa could only sign the agreement itself once the protocols had been filled in with actual tariff-reduction schedules and the like. Arguably it was because of concerns about competition from South Africa, that Nigeria got cold feet at the last moment.

Another major concern that Kaberuka acknowledged, is that Africa lacks the infrastructure – roads, railways, bridges, ports – to carry the greatly increased volumes of trade that the AfCFTA is meant to enable. He said the Single African Air Travel Market for Africa had been launched to intensify commercial links and lower the costs of doing business. The AfCFTA would also be accompanied by an African trade development plan of action to address trade-related infrastructure; trade finance; payment systems; investment policy harmonisation; and the movement of people.

In fact, the protocol on the free movement of persons – including the right to live in and set up businesses in other countries – was also signed at about the same time as the AfCFTA, underlining the AU’s commitment to open up commerce across the continent.

The loss of revenue from the scrapping of import tariffs remains a major concern, especially for smaller countries with no significant alternative domestic tax bases. Some will probably be net losers at first. They will have to move quickly to attract productive investment to take advantage of the AfCFTA, mindful of Karingi and Mevel’s finding that those who don’t join the AfCFTA will likely be worse off than now when it enters into force. For larger industrial powers (notably South Africa), the AfCFTA looks like an unambiguous plus – as Rob Davies, the country’s Trade and Industry Minister confirmed, when he said that Pretoria was completely committed to it.

Last year, Davies noted, South Africa exported US$23.5 billion worth of goods to the rest of the continent, and imported just US$8.6 billion, racking up a huge trade surplus of US$14.9 billion, which will only grow bigger under an AfCFTA.

Some sceptics have suggested that if the earlier Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) merging SADC, the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, and the East African Community had been properly put into operation before the AfCFTA was launched, it would have enhanced the credibility of Africa’s trade liberalising intentions. However, South African officials counter that the two free trade agreements (FTAs) offer different benefits, and that launching the AfCFTA now potentially opens up the lucrative West African market in particular to South Africa more quickly.

Many unknowns still remain in trying to predict the AfCFTA’s impact. With a dearth of hard data, most commentators and principals (including Adesina) latched onto Karingi and Mevel’s calculations – namely that, by 2022, the AfCFTA would boost intra-African trade by 52%, increasing the continent’s share of such trade to 115.5%.

Though, as Karingi says, much has changed since that report was done and they are now updating it. The changes point both ways.

On the one hand, African countries have moved faster than predicted with trade liberalisation efforts, both bilaterally and in regional FTAs. Last year the share of intra-African trade had already reached 15.28% – which is about where Karingi and Mevel estimated it would be, but only in 2022 and only with an AfCFTA.

On the other hand, Karingi notes that they based their calculations on a 100% opening of the market, whereas in its final form the AfCFTA will open just 90% of markets. ‘But our results earlier had not included services trade, which will now be opened up including transport, communication, finance, tourism and business services,’ he says, indicating that liberalising services will also provide greater benefits.

What is clear, even so, is that a properly implemented AfCFTA would be good for Africa and that it would be much better still if it were implemented with extensive trade facilitation measures as well.

However, as Kaberuka has pointed out, easing these and other non-tariff barriers – such as accelerating the flow of goods across borders through cutting red tape and corruption, dismantling road blocks and making ports more efficient – will be harder than scrapping import tariffs. They will require much more political will. Needless to say, the continent’s destiny is, as ever, in the hands of its leaders.