The issue of electrical transmission systems in Africa has received limited coverage compared to that enjoyed by the generation component of the system. Yet as consultants McKinsey noted in 2015, for every US$10 spent on generation capacity, Africa needs to spend US$7 on transmission if it is to overcome its serious power deficit.

Continent-wide transmission systems are a necessary part of Africa’s future development. According to Makhtar Diop, World Bank vice-president for Africa, ‘much of the focus in scaling up investments in the power sector has been on upstream generation capacity investment’. But he argues, ‘a primary cause of the continent’s poor quality of supply and low electrification rates lies with weak power networks’, and that ‘without these transmission investments, there is a high risk of creating system bottlenecks, leaving generation assets stranded’.

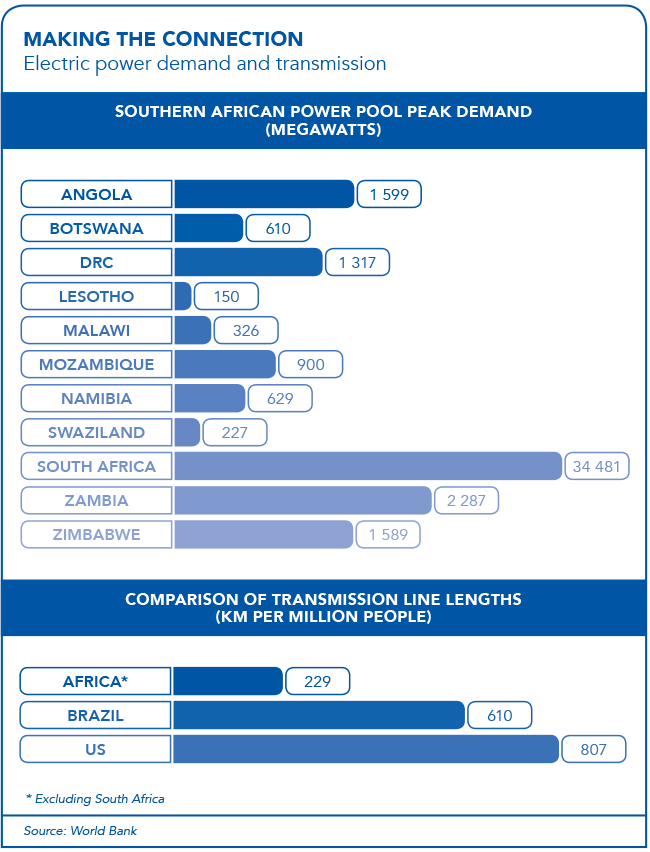

The World Bank’s 2017 report, Linking up: Public Private Partnerships in Power Transmission in Africa, points out that Brazil has a longer transmission network (125 640 km) than nearly 40 African countries combined (112 196 km). Nine of those African nations have no transmission lines above lightweight (non-industrial) 100 kV capacity.

Kieran Whyte, of consultancy Baker McKenzie, says that demand for electrical power on the continent does not necessarily coincide with the occurrence of natural resources for generation. ‘It’s about moving the electron,’ he says. Whyte adds that ‘enhanced transmission infrastructure is the only way to get power from the point of generation to where it is needed’.

Transmission needs to happen between countries. Whyte highlights that there is much to be gained from ‘having the capacity to move the electron from Ethiopia, where there are currently huge generation projects under way, to other countries like Kenya, with its emerging industrial demand’. However, he also emphasises that much development of national and sub-national grids is needed too. ‘This is essential if Africa is to move away from being a commodity-driven continent and if it is to move into sustainable development.’

Industrial development requires stable and affordable power supply, which is why the AU has thrown its weight behind a number of major regional transmission programmes.

The 2 000 km West African Power Transmission Corridor runs from Nigeria to Guinea. It has a planned transfer capacity of 1 000 MW and is expected to cost an estimated US$1.2 billion. The 3 800 km Central African Interconnection will reach from Chad in the north to South Africa. It will have a transmission capacity of 17 000 MW and cost about US$10.5 billion. The North-South Power Transmission Corridor will run all the way from South Africa to Egypt, a distance of some 8 000 km, while the North African Transmission Interconnection will run from Morocco in the west to Egypt in the east.

These macro-programmes are perhaps best seen as being made up of smaller components that will eventually be joined up. While progress is happening across Africa, the present public sector-driven model means much of the potential interconnectedness of the continent will be hamstrung by the lesser capacities of the financially weaker countries involved. The key drivers are the regional power pools in Southern, East, Central and West Africa. The project to link the Southern and East African power pools depends on a connection from Zambia to Kenya via Tanzania – the ZTK power interconnector.

The ZTK interconnector is the transmission link that will make it possible to push an electron from Cape Town to Cairo and vice versa. But the three countries involved are moving at different paces. The Kenyan section is fully financed and already under construction but the other two countries still have to secure finance. Zambian needs US$160 million and Tanzania US$425 million.

In Southern and Central Africa, a number of significant elements do seem to be coming together. In February, it was announced that the feasibility study for the US$223 million Zizabona interconnection was complete and has been presented to the AfDB, which funded it. The project is named after the first two letters of the four countries concerned – Zimbabwe, Zambia, Botswana and Namibia. It is intended to connect current and future hydroelectric plants in the four countries and, in so doing, ‘decongest’ the Central Transmission Corridor, which runs from South Africa northwards through Zimbabwe to Zambia and potentially beyond.

Limitations on transmission infrastructure have been the main reason for limited trade within the Southern African Power Pool (SAPP). Then South African Energy Minister, Mmamoloko Kubayi, said last year that it was possible to trade only about one-third of the power available and demanded because of infrastructure constraints.

On the generation side, according to reports, SAPP member states commissioned 4 180 MW of additional generating capacity from new projects and the rehabilitation of old power plants. Projects were commissioned by both public utilities and independent power producers. The generation mix for the new power plants commissioned in 2016 came from hydro (43%), gas (24%), solar (11%), wind (10%), coal (7%) and diesel (5%).

Botswana has excess capacity and recently announced in March that it is exporting power into the SAPP for the first time in a decade.

Botswana has previously had to import as much as three-quarters of its power requirement. Its new-found over-capacity has been made possible by improved plant availability at the flagship 600 MW Morupule B plant, which is now producing 450 MW and will soon reach full capacity.

Botswana’s exports will rise when the 120 MW Morupule plant comes back on-stream in July, following a six-year refurbishment programme.

Whyte says that transmission is a regional integration issue in Africa. It is part of the trade facilitation agenda and no coincidence that the main planned transmission networks follow the major trade corridors, alongside other infrastructure, including road and rail links. ‘From this perspective, the electron should be seen as another commodity, to be traded between national markets.’

A key part of the Central African Inter-connection is the transmission line between Zambia and the DRC.

‘Options being considered for this transmission line are to connect Kolwezi in the DRC to the district of Solwezi in Zambia, through the Zambia Electricity Supply Corporation network at Lumwana or Kalumbila substation and the future Société Nationale d’Electricité network at Kolwezi NRO substation,’ says Andrew Galbraith, director: transmission and distribution at WSP Power Africa.

‘A team of engineers from WSP have been appointed to develop the transmission line and will undertake a three-stage feasibility study to develop options and recommend a preferred solution for the interconnector. This will include initial assessment of the routes and substations; data gathering; financial and economic analysis; detailed route surveys; and detailed design and specifications. A big issue – and one that is only now being dealt with – is how this needed capacity will be financed.’

McKinsey estimates that the African market for transmission (and distribution) will be worth some US$345 billion between 2015 and 2040. The World Bank suggests that the annual investment requirement for transmission alone, over the same period, is US$3.2 billion to US4.3 billion. But transmission in Africa is traditionally a state run and financed function. This must change.

Diop points out that ‘there is a disproportionately large funding gap affecting sub-Saharan Africa’s power sectors that cannot be met by the limited public finances of client countries alone’. The only solution, he says, is to draw more private finance into transmission.

The 2017 World Bank report on the issue points out that transmission has traditionally been regarded as a ‘natural monopoly’ and that almost all transmission in Africa is financed by state-owned enterprises. But, it says, ‘public finance is relatively scarce in fiscally constrained environments’. This was the situation in the rest of the world until the 1990s. Since then, however, a wave of restructuring – especially in Latin America – has demonstrated that the private sector can be successfully introduced to what once seemed to be a quintessential public sector venture.

The solution advocated by the World Bank is an independent power transmission (IPT) model, which falls short of alternatives such as full privatisation and ‘whole of the grid concessions’. IPTs are where a single transmission line or package of a few lines are run by a private sector concessionaire on a long-term contact, with payment dependent on the availability of the line.

The finance-raising modalities of IPTs are essentially project based and thus very similar to the project finance models that have gained so much traction in Africa’s power generation sector in recent years.

Governments, financiers and the multilateral institutions have accumulated sufficient knowledge and understanding of the model to make it viable. ‘Project finance can allow state-owned utilities to raise additional capital that would otherwise be unavailable by separating out a portion of cash flows related to particular investments,’ says the World Bank.

This is the model that has worked well in India, Peru, Columbia, Brazil and Chile. The World Bank also notes that many African countries are at the same levels of development, in terms of per capita incomes, as were other developing countries when they introduced IPTs. Kenya has a GDP per capita of US$1 113 and Nigeria US$2 535 compared to Peru’s US$3 266 in 1998 when IPTs were introduced and India’s US$1 056 in 2006. Southern African countries such as South Africa, Namibia and Botswana are well ahead of these benchmarks.

This, in the World Bank’s view, indicates that these African markets are ripe for private sector involvement in power transmission. The bank does, however, suggest proceeding cautiously ‘and only in selected countries’. Nevertheless, this new insight into financing dovetails well with the regional interconnection projects already under way.