You don’t see it coming. As the drone flies over St Ives gold mine, the onboard camera offers a perfect bird’s-eye view of the semi-arid western Australian landscape below. The horizon curves up ahead as you rise up above the mine site, 20 km outside the small town of Kambalda and, while you’re watching the ground – flap-flap-BANG! – a wedge-tailed eagle swoops out of nowhere and spectacularly knocks the drone out of the air. (You can watch the footage on YouTube.)

Australian eagle 1, drone 0. Or, as the headline on tech website CNET tells it: Australian eagles 9, drones 0.

Gold Fields has been using drones – more correctly known as unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs – since at least mid-2014, and it has lost nearly a dozen of them to Australia’s largest birds of prey. ‘That bird is my single-biggest problem in the environment where I work,’ surveyor and drone pilot Rick Steven recently told colleagues at the Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy’s Open Pit Operators’ conference in Kalgoorlie. ‘I am on my 12th [drone].’

With each UAV costing around AU$10 000 and the onboard camera priced at about the same, these attacks are proving to be an expensive act of nature for Gold Fields. But it’s a cost the company is willing to absorb, given the value-add presented by drone operations.

Drones are considerably cheaper to use than helicopters, allowing mining companies to survey new areas and provide better results at a fraction of the price. Those benefits are felt across the value chain, from search and rescue operations to exploration, mine mapping, stockpile mapping and remote sensing.

In northern Canada, Rio Tinto uses drones to measure the volume of piles of crushed rock (usually 3 million tons of it) at its Diavik diamond mine. That rock is being used to build a massive dyke to access the project’s new kimberlite pipe. Now, thanks to drones, a job that used to take two surveyors a few days to complete on foot can be done in less than an hour at far lower risk.

‘You’ve got moving equipment, ’dozers and trucks. You don’t want people on foot in the mix there,’ engineering superintendent Gord Stephenson told CBC News.

‘We’ve used it in inspections in open pits. We can no longer see the floor so we have been able to provide regular updates and imagery to the underground mine to help them plan some of their work. I think we’re just tapping into the potential applications here.’ Across the world, those potential applications are ‘potentially’ limitless. And they’re not confined to work above the ground.

Fred Cawood, director of Wits University’s Mining Institute, recently told Reuters that drones are now being developed to send to danger zones below the surface. ‘It’s to use the machine in areas where people should not be,’ he said, adding that a small, 40 cm prototype equipped with video cameras is currently under development. To operate in the tunnels, ‘it can’t be very big’.

Unmanned drones are part of a wave of digital innovations that are radically changing the global mining industry. And that change is desperately needed.

In August, natural resources and environment executive director at the CSIR May Hermanus told the MineSafe conference that if there was no substantial change in the mining methods used in South Africa, gold and platinum mining could cease by 2033 and 2029, respectively. ‘It is very clear that if we do not do anything and face up to challenges facing the sector … we will simply run out of options on how to proceed.’

Those sentiments were echoed a month later by Telstra Mining Services head Jeanette McGill. ‘I really believe that the mining sector requires disruptive change,’ she told the 2016 Electra Mining Africa exhibition in Nasrec, Johannesburg. ‘Definitely the interaction of people, process and technology is going to be key to support this disruptive change.

‘Connectivity is key. It is how we are going to get the data to shift and how we are going to use the data throughout the technology stack and support this digital era of global connectivity 4.0.’

That notion of 4.0 – referring to the fourth industrial revolution, which will garner total connectivity of mining businesses across the supply chain – was a recurring theme of the conference, as was talk of the so-called intelligent mine, where real-time data informs automated responses and removes the risk of human error.

That promise is particularly compelling at this point in the history of the African mining industry. ‘The current economic climate leaves no room for error in mining, and companies are unwilling to compromise on safety, expecting the most state-of-the-art and cost-effective solutions,’ Dirk van Soelen, global portfolio manager at AEL Mining Services, said in a company statement. AEL recently launched its IntelliShot Electronic Initiating System, which is able to wirelessly tag and test up to 300 detonators per line – bringing unprecedented levels of safety and automation to the blasting process.

Harry Sinko, MD of web-based contract mining firm NxGN, told the Electra Mining Africa conference that digital disruption would involve far more than simply the introduction of new technology.

‘It’s actually all about creating new business models that disrupt the industry, [and] change the way the industry works,’ he said. Sinko illustrated his point by comparing productivity in the automotive and mining industries. ‘The mining industry has been losing ground since the early 2000s, whereas the motor industry is starting to climb really high.’

There is a degree of cross-over, though. Motor manufacturer Volvo recently launched a self-driving truck (in essence, a fully kitted-out construction vehicle) that is able to navigate and operate entirely autonomously, both above and below ground.

The truck uses sensors and GPS technology to continuously read its surroundings, navigating fixed and movable obstacles while gathering data via its transport system to further optimise its route and traffic safety.

The applications for mining are obvious: it requires no manual supervision. Perfect for long, dark tunnels.

‘We do things to make our customers more profitable,’ Volvo’s chief technology officer Torbjörn Holmström said in a statement. ‘The difference between us and the car industry is that we don’t just add technology for the fun of it: there has to be a business case.’

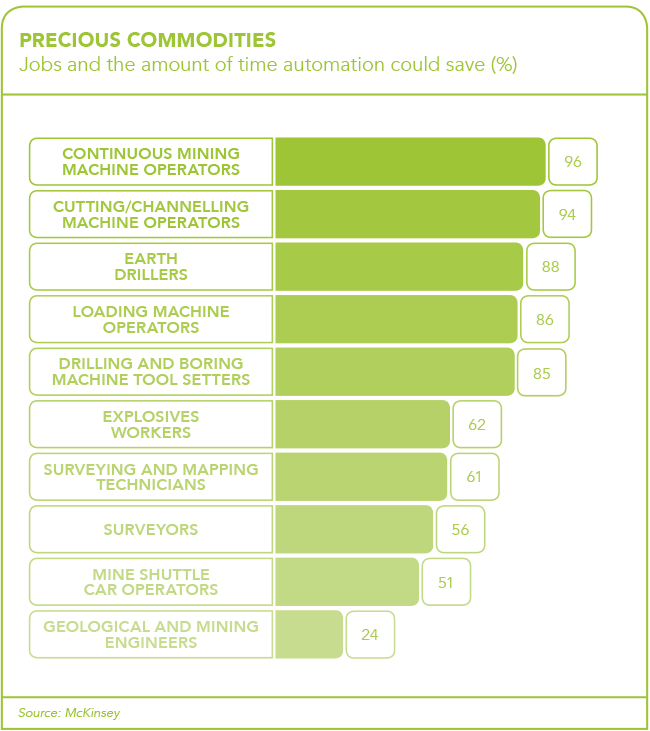

There is – and it’s quite compelling. According to researchers from Canada’s University of British Columbia, when applied to mining operations, driverless technology can bring about a 10% to 15% decrease in fuel consumption, an 8% decrease in maintenance costs, and a 15% to 20% increase in output. The impact on labour costs is, of course, also significant.

Across the world – and in South Africa especially – urgent research is being conducted into smart surveying and mapping systems, energy savings, smart rock-engineering systems and data processing. And as Africa moves closer to the intelligent mine, the continent is already adopting a series of promising disruptive technologies.

Jonathan Spencer, Barloworld Transport IT executive, recently spoke about new business models in freight movement, including truck platooning and central data analysis. Truck platooning sees two or three trucks linked in close convoy through connectivity technology and automated driving-support systems. The trucks share a constant communication link that allows them to match each other’s speed and braking automatically – thereby improving safety and fuel economy.

‘Platooning is also a cost-saver as the trucks drive close together at a constant speed. This means lower fuel consumption and fewer CO2 emissions,’ Spencer said in a media release, adding that platooning is the first major move towards completely driverless trucks.

‘Anyone can buy a truck and move stuff around,’ he said. ‘The differentiator is if it’s done smartly and efficiently, and in a way that adds value to the customer and makes our roads safer. More information and automation leads to better and safer decisions as to how the truck should run, provided that someone is actively using the data that is produced.’

Technologies such as unmanned drones, electronic blasting systems and driverless trucks are spearheading the rise of the intelligent mine. Yet, in a sense (and much like that Australian eagle), they seem to have come out of nowhere. The technological advances have been fast and sudden, and not all mines or mining companies are entirely ready for them yet.

‘Digital technologies are fundamental for efficient and safe mining where all systems are optimised, and this requires clarity of multiple sources of underground data, communicated to a surface control room and back to the workplace in real time,’ Bekir Genc of Wits University’s School of Mining Engineering said at the opening of the 2015 Mining into the Future conference.

‘This is not happening yet. It requires an enormous amount of work, but some parties have started trying to establish these systems.’

From Australia and Canada to South Africa and beyond, the digital revolution is happening everywhere. And, Genc said, it will inevitably happen to the mining industry: ‘If not today, tomorrow.’