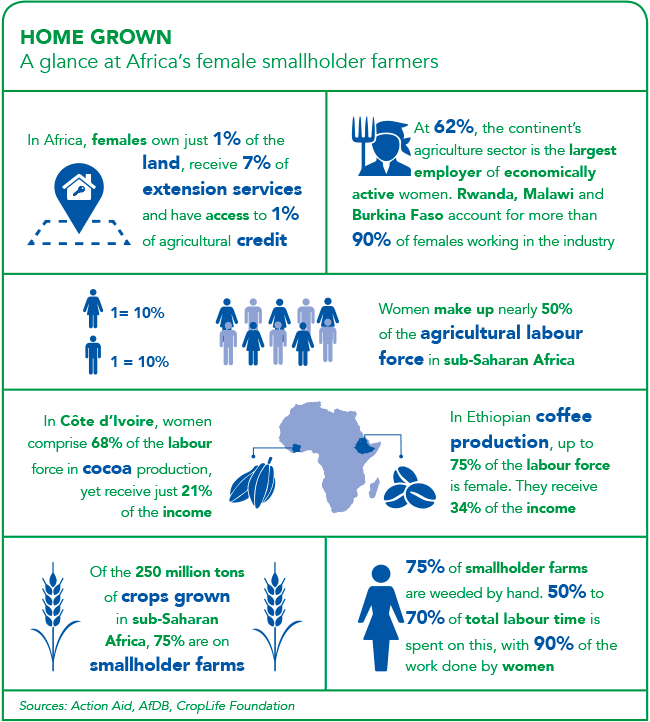

The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) estimates that women make up on average 40% of the agriculture labour force in developing countries, with this figure climbing to as much as 50% or even 70% in parts of Africa.

Despite this, women continue to find themselves in a disadvantaged position, lacking access to financial services, land, equipment and technology, struggling to gain entry to markets, and earning less than male farmers. They also risk personal injury and harm in their households and communities, depending on customary and cultural norms.

‘Increasing rural women’s access to decent employment opportunities is key to improving their productivity and earning power, which in turn raises family incomes and food security,’ the FAO states on its web portal.

Closing the gender gap has thus been identified as one of the most effective ways to promote agricultural development, combat poverty and empower women. According to Farming First, a global coalition of organisations that advocate the development of sustainable agriculture, a significant gender gap does indeed exist in the sector.

‘The vast majority of studies have found that differences in yields between men and women exist not because women are less skilled, but because they have less access to inputs such as improved seeds, fertilisers and equipment,’ it states.

The organisation says that in sub-Saharan Africa, just 15% of landholders are women, and they receive less than 10% of credit and 7% of extension services. In terms of access to inputs and technologies, women again receive a smaller percentage than their male counterparts.

Moreover, women farmers typically achieve yields that are 20% to 30% lower than men. Studies show, however, that women farmers are just as efficient as men, and would achieve the same yields (if not higher) if they had equal access to resources and services. This could boost total agricultural output in developing countries by 2.5% to 4% – enough to reduce the number of undernourished people in the world by between 100 million and 150 million, says the organisation.

Farming First has acknowledged the need for more inclusive policies to help rural women thrive. So has Saquina Mucavele, executive director of a Mozambican non-profit MuGeDe. In a paper on the role of rural women in agriculture, Mucavele notes that many African countries have begun adopting new land laws in order to strengthen women’s land-ownership rights, with matters of policy also receiving more attention, and governments paying more attention to the agricultural sector than before.

‘The lack of appreciation of the role of rural women in agriculture is harmful and gives rise to a lack of specific policies. Policies that are misdirected, high levels of poverty, illiteracy and non-involvement in the design and planning of programmes and policies, which involves a process of mutual learning that reflects the real and specific needs of rural women,’ she wrote. ‘Realising the importance of rural women in agriculture is an important aspect of gender relations.’

Mucavele added that policies established for the benefit of rural women should be tested and reassessed by the beneficiaries, and used as social-learning tools. ‘Giving support to rural women is a way of breaking the vicious cycle that leads to rural poverty and to the expansion of slums in the cities.

‘Development strategies should consider rural women as the epicentre, paying special attention to their social skills both within and outside the agriculture sector,’ she wrote.

Nicolas Mounard, CEO of Farm Africa, a charity organisation that supports farmers in East Africa, says it is rare to see a gender-specific approach to a value chain or agriculture – something he believes is crucially important. ‘I’m a big advocate for developing specific methodology. Gender roles should be seen differently,’ he says.

Mounard adds that in agriculture, not only are women doing most of the work, but they also perform the majority of the strategic processing steps, where both productivity and quality are at stake. ‘So from a value chain perspective, to upgrade the quality of the product and boost productivity, you must work with women, as they are heavily involved in all areas,’ he says.

When it comes to addressing the many challenges that these women face, Mounard believes the starting point is visibility. ‘It’s one thing to say women are doing the jobs in agriculture, but which women?’ he says. To best assist those who need it, and for them to be the beneficiaries of training in good agricultural practices, Mounard says they must know which women they are helping.

‘For that we have a methodology where we create women’s groups at village level – be they formal or informal – to create a structure that makes these women visible. This helps us channel all the technical assistance to the women who need it,’ he says.

‘Differences in yields between men and women exist not because women are less skilled, but because they have less access to inputs’

With regard to access to land, Mounard notes that this challenge is country-specific and requires a sense of the customary rights and legal framework of each state. In some cases, a joint-land agreement must be discussed at a household level, or effort must be made with regard to formalising ownership for the women in the household.

A more pressing issue, he says, is managing the side effects of working on women’s economic employment, as this can lead to violence against women. ‘You create some tension when you start working on these sorts of things because you are changing traditions,’ he says. ‘If you come with a large-sized budget, the perception of the community is that you’re working only with a part of the community, the women in that case, and you are leaving the men out. It creates frustration, so you need to manage that dynamic.’

Farm Africa has seen immense success in the countries it operates in. Telesia, a single mom in rural Kenya, has gone from struggling to feed her family to becoming a successful business woman, thanks to Farm Africa. She joined the programme in 2005.

‘We were given local goats to cross with a dairy-goat breed for milk production, and as I was the only person in the group who understood English and spoke Swahili, I was trained as a community animal health worker,’ she says.

Telesia was also trained to run a savings and loan credit group, for which she was eventually elected treasurer. Through her involvement with Farm Africa, Telesia was able to borrow enough money to start a business selling petrol, diesel and kerosene; open up a shop; and extend her farm plot to grow more produce. As her various ventures grew, so too did her income and personal successes, culminating in Telesia being identified as a leader of the Uwezo Fund, a government financing channel for women and youth. Her goal is to educate her children – the oldest of whom is currently studying medicine.

Medeatrice, a farmer in Rwanda, received her helping hand from the One Acre Fund, which operates in Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Malawi, Tanzania and Kenya. One Acre provides support to smallholder farmers, including financing for farm inputs, distribution of seed and fertiliser, training on agricultural techniques, and market facilitation. It currently represents Africa’s largest network of smallholder families, and estimates that by 2020 it will serve more than 1 million farm families, helping in excess of 5 million people.

Prior to signing up with the fund, Medeatrice struggled to make farming profitable – her yields were low and she had difficulty accessing markets. In her first harvest with the fund, she produced more than twice what she ordinarily would, making enough money to invest in a small shop, which her husband now runs. Their dream is to see their son attend university, and Medeatrice says they see farming as a pathway to achieving this.

In South Africa, many large organisations (especially those in the food-retail sector that work a lot with agricultural-produce suppliers) consider sustainable enterprise development and small business incubation as key to lifting people out of poverty and empowering entrepreneurs. Pick n Pay, through its philanthropy arm, the Ackerman Pick n Pay Foundation, links emerging farmers to its stores, thereby giving them easier access to markets – a notorious challenge for entrepreneurs.

The company purchases short- and long-term crops from farmers, while perennials are bought by manufacturers for processing, thereby providing the farmer with consistent cash flow.

Moreover, as part of its long-term strategy, Pick n Pay designed a franchise model that provides a point of convergence between the community, local suppliers and retailers. Such stores are established through a partnership between the community, local suppliers and commercial banks. Communities purchase produce from the local store, which is linked to subsistence farmers close by, and which thus receives a direct supply of fresh produce.

For Woolworths, having a diverse supplier base is a business sustainability imperative, says Zinzi Mgolodela, the company’s head of BEE and transformation. Woolworths runs an enterprise and supplier development programme that engages with businesses on their productivity, business growth, governance, and the operational sustainability of their enterprises. The programme includes, among others, agriculture and agri-processing businesses, and Mgolodela says the company places emphasis on emerging farmers, who she describes as ‘crucial to the sustainability of our supply chains’ in South Africa.

‘First and foremost, the programme seeks to remove the barriers of entry into the Woolworths supply chain for small, medium, black- and black-woman-owned enterprises,’ she says.

‘We have, over time, helped create many small, black-owned and black-women owned businesses, that are flourishing and have become meaningful elements of our supplier base with visible commercial returns.’