Hydropower is responsible for generating the largest share of electricity globally – so much so that it has been called ‘white coal’. According to the International Hydropower Association (IHA) and its 2020 Hydropower Status report, there is currently 1 308 GW of installed hydropower capacity globally, with approximately 15.6 GW of hydropower capacity put into operation in 2019 (compared to 21.8 GW in 2018).

The continent has the highest percentage of untapped technical hydropower potential in the world, with just 11% utilised, the IHA reckons. In 2019, 906 MW of hydropower capacity was put into operation in Africa. Out of the 48 countries around the world to add hydropower capacity last year, seven were African, the top five being Angola, which added 334 MW, followed by Uganda (260.45 MW); Ethiopia (254.1 MW); Cameroon (45 MW); and Malawi (8.2 MW).

The Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (supported by the AU and AfDB) considers hydropower development a priority, estimating that the region’s total generating capacity needs to increase by 6% per year to 2040 to keep up with the continent’s rising demand for electricity.

Wale Shonibare, the AfDB’s acting VP of power energy, climate change and green growth, speaking at the Africa High-level Sustainable Hydropower Roundtable held in February this year, highlighted the immense potential that hydropower could offer the continent. ‘As a renewable-energy source offering design options – from run-of-river to pumped storage plants – hydropower, in its different forms, adds significant value to power systems and the reliability of energy supply,’ he said. ‘As the bank’s emphasis on renewable-energy sources is growing, so too is its interest in hydropower.’

Indeed, the AfDB has demonstrated its commitment to supporting new hydropower projects through its New Deal on Energy for Africa, having already invested close to US$1 billion for 1.4 GW of expected installed capacity over the past decade.

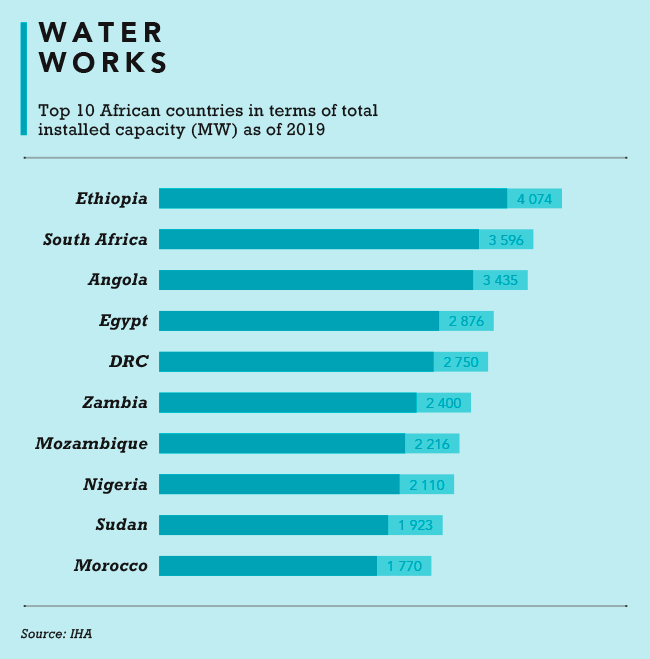

The continent has more than 37 GW of installed hydropower capacity, notes the IHA. Ethiopia, at 4 074 MW, tops the list of African countries with installed capacity exceeding 2 GW, followed by South Africa, Angola, Egypt, the DRC, Zambia, Mozambique and Nigeria.

South Africa has a mix of pumped-water storage schemes and small hydroelectricity stations. Although the country has the second-largest installed hydropower capacity in Africa, it produces less than 5% of its total electricity in this manner. Activity has slowed in recent years, but hydropower development is still taking place, albeit not at the same rate as wind and solar projects.

Among the most recently commissioned large projects is the Ingula pumped storage scheme in KwaZulu-Natal, which commissioned its fourth and final generator in early-2017. The scheme consists of an upper and lower dam, each capable of holding approximately 22 million m3 of water. The dams, located 4.6 km apart, are connected by underground waterways passing through a subterranean powerhouse with four 333 MW generators, giving it a total rating of 1 332 MW of installed capacity. The project cost a total of ZAR25 billion.

Another of South Africa’s more recent hydro builds is the Neusberg project, owned by Kakamas Hydro Electric Power. This small, run-of-river (in other words, little or no water storage) hydropower project on the Orange river near Kakamas in the Northern Cape delivers 10 MW of baseload power to the grid – enough electricity for 5 000 homes. Construction started in June 2013 and the power station began commercial operation end-January 2015.

It was the first run-of-river hydropower scheme developed under South Africa’s Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement (REIPPP) programme.

The Stortemelk hydro project in the Free State, which achieved commercial operation in 2016, is another hydropower initiative under the REIPPP. This 4.5 MW plant, developed at a cost of ZAR190 million, set a benchmark for small hydropower (SHP) in terms of design and performance.

The UN’s Industrial Development Organisation, in a 2016 report on SHP development globally, notes that South Africa’s REIPPP programme had initiated ‘substantial activity’ in hydropower. Installed capacity of SHP stood at 50 MW, although the potential was estimated to be 247 MW. In other words, just 20% had been developed.

Studies undertaken over the years indicate unexploited potential is still available – particularly in the rural areas of the Eastern Cape, Free State, KwaZulu-Natal and Mpumalanga – but any future builds in South Africa are likely be on a small scale.

The situation is quite different elsewhere on the continent, with numerous large-scale projects currently in development. According to the IHA, Africa’s hydropower installed capacity is expected to grow by 23% by 2040.

Major projects currently under development include the Caculo Cabaça hydroelectric facility (Angola), Kafue Gorge Lower power station (Zambia), Zungeru (Nigeria) and Karuma (Uganda). Among the projects that have recently been commissioned are Lauca (Angola) and Isimba (Nigeria).

The 700 MW Zungeru hydropower project, which is being constructed on the upper and middle reaches of the Kaduna river in Nigeria’s Niger State, is the largest hydropower project currently under way in the country. At an estimated cost of US$1.3 billion, it is also one of the biggest power projects in Africa to have received financing from the Export-Import (Exim) Bank of China. Due to come online in 2021, the facility will produce enough power to meet close to 10% of the country’s total domestic energy requirements.

In Zambia, the 750 MW Kafue Gorge Lower power station was on schedule to be fully commissioned by the end of 2020, although the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdowns have caused delays. According to reports, the units will be synchronised in a phased approach.

In Angola, the government hopes to achieve a 60% electrification rate and has undertaken a strategic environmental assessment to evaluate its 18 GW hydropower potential as part of its 2025 strategy. The Lauca hydropower project is currently the largest hydropower plant in Angola, at 2 070 MW. However, this accolade will soon be handed to the Caculo Cabaça project. Set to comes online in 2021, it will have the capacity to produce 2 172 MW of power. Once both are online, close to a third of the national target of 9.9 GW of installed generation by 2025 will be met.

Earlier this year, technology group Voith signed an MoU to build a training centre in Angola, which will provide theoretical training and professional development to skilled workers in the country’s hydropower sector. For the practical component, Voith will work with the trainees to build a small hydropower plant in the Cuemba region.

Hydropower around the continent is set to receive yet another boost – this one financial, provided developers are doing good business. The Hydropower Sustainability ESG Assessment Fund was announced in February. It will award US$1 million to at least 40 hydro projects between 2020 and 2024. Recipients will receive a grant to part-finance the cost of commissioning an independent project assessment using Hydropower Sustainability ESG Gap (HESG) analysis, a tool that enables hydropower project proponents and investors to identify and address gaps against international good practice.

‘This initiative will encourage renewable-energy proponents to draw on international good practice when planning and implementing hydropower projects,’ according to João Costa, senior sustainability specialist at the IHA, which is managing the initiative.

‘Commissioning an HESG assessment helps guide developers and operators to address any gaps in environmental and social performance. Going through this process will ultimately demonstrate a project’s sustainability and help unlock green finance.’

The first tranche of funding for 2020 will be made available for projects in numerous countries, with those in Africa including Egypt, Ghana, South Africa and Tunisia.

By Toni Muir

Images: Gallo/Getty Images