In early 2019, big four auditor PwC measured stock at German energy firm RWE’s coal-fired power plant in Aberthaw, South Wales. It was fairly routine stuff, involving a stock-take of the plant’s coal reserves – a task that would normally be done manually, taking about four hours. This time – and for the first time – PwC used a drone for the job. The unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) captured more than 300 images of that coal pile and finished the task in about 30 minutes.

‘While the traditional method remains reliable and will still be used for RWE’s formal year-end financial statements, the drone trial was conducted to explore ways of challenging the traditional method of stock counting,’ according to PwC audit partner Richard French. ‘It was a classic example of new technology challenging the old – and based on our results, the potential is groundbreaking.’

Drones are lighting up the skies around the world – both as birthday gifts and as increasingly useful business tools. Ruan Botha, product manager at South African ICT company Rectron, notes that drones can play a role in ‘optimising operations across a wide range of different sectors’ – so much so, he says, that the drone industry was estimated to have had a turnover of almost ZAR6.5 billion in 2017 in South Africa alone, representing a six-fold increase on 2015’s figures.

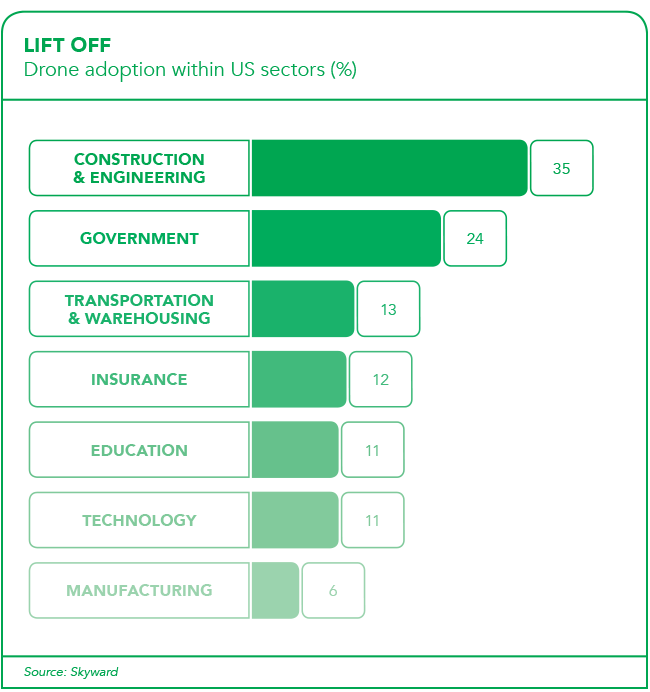

In the US, meanwhile, the Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) recorded more than 1 million drones sold countrywide by the end of 2018. By the end of 2019, the FAA expects that number to more than double, reaching in excess of 2.4 million units. Many of those drones are sold to private buyers for personal use. But as the technology matures and as the market grows, more and more industries are finding a use for those lightweight, mechanical ‘eyes in the sky’.

Last year the AU’s executive council requested the AU and member states to ‘harness drones for agriculture’ as one of three emerging technologies of relevance for African development. The other two identified technologies were micro-grids to provide Africa with electrical power, and gene drives to eliminate malaria on the continent.

Alongside power grids and deadly diseases, drones may seem the odd one out… But not to industry insiders such as Dave Estment, owner of South African drone imaging company Outdoor Video & Photographic. Estment says that about 40% of the aerial work OV&P does now is for construction firms, banks, energy companies, game reserves and the like. ‘We have been approached on a number of occasions to do surveying of mines, quarries, farming activities and so on,’ he says. ‘We refer these jobs to colleagues of ours who specialise in this genre of drone work, which is fairly structured, mainly flying pre-planned grids at fixed speeds, altitudes and specific grid sizes to provide accurate data; to create detailed 3D maps on apps like Pix4D.’

The question of how African businesses can use drones is then best answered: it depends on what you want, and what line of business you’re in. Anglo American subsidiary Kumba Iron Ore, for example, is using a small fleet of drones to optimise the surveying processes at its famous Sishen mine in South Africa. ‘Routine tasks historically carried out by surveyors, such as measuring the volume of waste dumps and stockpiles, are now being done by our drones,’ says Bongi Ntsoelengoe, technology manager at Kumba Iron Ore. ‘The drones collect digital imagery that is pieced together to perform volume calculations, giving us reliable data without having put anyone at risk.’

Kumba’s drones also assist in inspections of hard-to-reach engineering equipment, eliminating the risk to human surveyors and improving survey turnaround times. In fact, Kumba has seen such a return on its investment in drone technology, that it has worked through a complex two-year legal process to earn an operating licence to fly its own drones, with its own staff licensed as drone pilots. Kumba’s experience suggests that – at least when it comes to drones – the widespread fear that automation will lead to job losses may well be unfounded. People employed on rope access teams, for example, might worry that their work in difficult (and often dangerous) aerial locations could be done with greater accuracy and at far lower risk by an aerial vehicle. Not so, says Mike Zinn, marketing manager at rope access company Skyriders. ‘There might be a few scopes of work where technology replaces human beings – like this very example you give of drone versus rope access – and that is why Skyriders was an early adopter of the technology,’ he says. ‘But the detailed follow-up scopes of work like NDT [non-destructive testing] and the repairs and maintenance scope of work that is generated by the drone inspections will still need to be carried out by human beings using rope access for many years to come.’

Skyriders recently completed a job at the Medupi power station in South Africa’s Limpopo province, in what Zinn calls ‘the perfect example of the synergies of using rapidly deployable drone technology alongside rope access’. As he explains, ‘the client needed a general overview of specific areas within the boiler within the first few days of the shutdown. This would need to be done without the traditional means of access [scaffolding], prior to boiler washing and prior to any other inspections. This would normally only be possible once massive scaffolding structures had been erected. Our Elios SkyEye team was able to inspect all the required areas from the safety of being outside the boiler. A detailed report was then drafted and presented to the client, and they were able to determine the follow-up scope of work based on clear, high-quality visual data’.

Meanwhile, across Africa, the farming sector is demonstrating how drones not only bring value to an established industry but can transform it entirely. As Yegen Naicker, MD of drone company RC Infinity, puts it: ‘We are now able to avoid conventional methods of aerial data collection and rendering of certain aerial services by replacing a helicopter or fixed wing plane with a drone. This results in an incredible decrease of CO2 emissions and safety risks linked to these operations.’

Naicker adds that farmers, for example, can now monitor and keep track of crop health by early detection of plant deterioration, pests, disease and harmful weeds. ‘By equipping a drone with specialised cameras that detect certain types of light – some not visible to the naked eye – we can now collect visual data of crops over large pieces of land and translate that data into useful and usable information for the farmer,’ he says. ‘By recording the types of light rays reflected off the plant matter or crops and the soil, we can determine the health state of the crop and take corrective measures where necessary.’

In Côte d’Ivoire, agritech start-up Investiv Group is doing precisely that: using drones to help local farmers carry out pre-farming studies on their land and conduct harvest forecasting with the aim of increasing production. This use of cutting-edge technology in a centuries-old industry is changing perceptions, and creating opportunities for surprising innovations.

As CEO Aboubacar Karim told the website IRAWO, ‘I want young people to understand that today you don’t have to take a daba hoe into the field to be a farmer. You can use a drone to spray a field; you can become a remote pilot specialising in agriculture; you can do agricultural imaging…’ And so the list goes on. It goes on, in fact, to include jobs and businesses such as StudEx Wildlife that (at this early stage) defy easy categorisation. The brainchild of Tumelo Ramaphosa, StudEx digitalises animals (including livestock), turning each into its own digital ‘coin’ that can be traded, sold or bred. It uses drones to fly around farms, monitoring the animals and keeping track of their health and whereabouts.

‘StudEx Wildlife and its operational partners are utilising drones in various forms already during the scaling and development phase of the business,’ says Ramaphosa. ‘These comprise fixed wing, rotary and – soon – aquatic drones.’ Ramaphosa says that drones serve as a sensor in the company’s quest to utilise multiple data sets in remote environments across the developing world. ‘The access to a bird’s-eye view enables insights that previously could only be enjoyed by industries with deep pockets,’ he says. ‘Drones are an enablement layer for emerging industries and entrepreneurs across the developing world.’

That last point would have been music to the AU’s ears. And while agriculture may be the focal point for now, other industries – from mining to auditing – aren’t far behind.