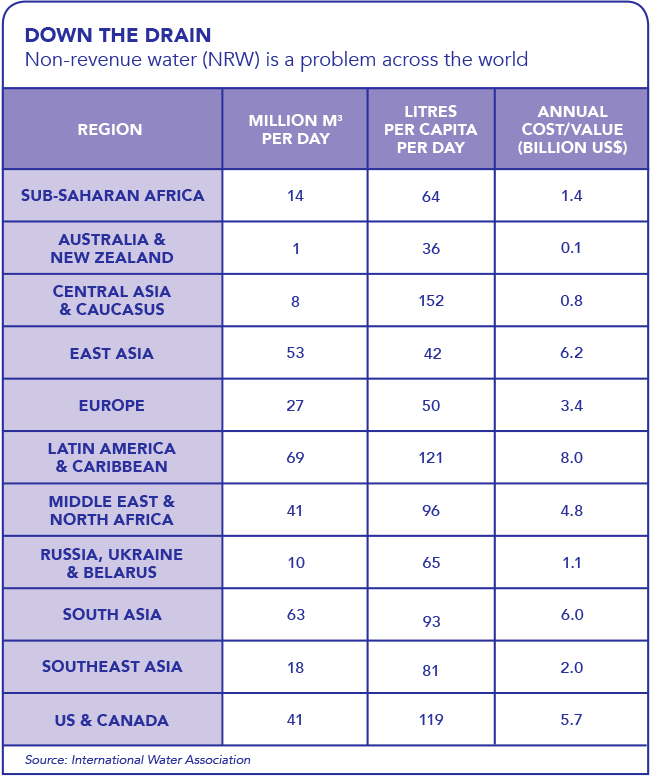

It would have been bad enough if the water had been washed down the drain. Instead, Kenya’s Nairobi City Water and Sewerage Company announced last October that it had lost KES1 billion of its water over the course of the previous year. It may have been due to theft or illegal connections, billing errors or faulty meters. Nobody knew for sure, and no one could tell where the water had gone.

Similar stories are told across Africa – including in South Africa, where the City of Johannesburg announced in May 2018 that it was losing between ZAR5 billion and ZAR8 billion every year because of revenue leakages and accounts being deleted off the billing system. Africa’s utilities, municipalities and consumers are drowning in a mess of inaccurate water bills, lost water and – ironically – chronic water shortages. For industry experts such as Darren Oxlee, chief technical officer at South African metering firm Utility Systems, the solution lies in keeping track of where the water is coming from, where it’s going, and exactly how it’s being used. This, he believes, requires smart metering technology. ‘Traditional water-management systems are rudimentary mechanical devices,’ says Oxlee. ‘Consumption readings are usually performed at most monthly and uploaded manually. This has two core challenges: reading accuracy, and the time lag between when the meter is read, uploaded into the municipality’s billing engine, bills generated and sent on to the customer. Any problems – such as leaks – are typically discovered weeks after the event, resulting in losses and associated costs.’

The ‘rudimentary mechanical devices’ that Oxlee mentions are able to measure water flow only. Smart meters, meanwhile, are water meters that are connected to electronic devices that either restrict the water flow or transmit the consumption data directly to a centralised database. Smart metering technologies typically include prepaid meters, automatic meter infrastructure, automatic meter reading, or a combination thereof. As Oxlee explains, ‘Utility Systems’ water-management system offerings include free-flow, flow limitation, electronic bailiff and prepaid water. The system as a whole is fully configurable according to customer requirements and allows the flexibility of, for example, switching between prepaid and post-paid by applying a configuration change to the device’. Smart by design, it supports ‘bi-directional communications for remote monitoring, configuration and management’.

Another way to keep real-time track of water use is via prepaid systems, where consumers can see how much they’re spending – or being charged for. Citiq Prepaid, for instance, has developed a sub-vending system that allows private landlords and managing agents to recover their electricity and water consumption data via a prepaid mechanism, which operates using a 20-digit token. ‘The token contains all the information, including the correct kilolitres or kilowatt-hours for the purchase amount for the tariff set for that specific meter,’ says Citiq Prepaid MD Michael Franze. ‘The funds collected from the tenant are pooled and then paid over to the landlord so that they can settle with the municipality or utility. In this way, even the utility or municipality is assured of improved payments rates from landlords.’

Franze notes that prepaid metering does not of itself guarantee accurate readings or billings, relying as it does on the underlying accuracy of the meter. ‘These are no more or less accurate than a post-paid meter.’ However, he adds that the prepaid mechanism improves billing because funds are collected upfront for the water service to be provided. The advantage of prepaid is twofold, he says. ‘The landlord gets the funds upfront and does not have to try to recover funds for a service already provided; and the tenant has a chance to learn what drives consumption in the household in real time, and isn’t left with nasty surprises months later when nobody can remember what caused the high consumption.’

Utility Systems’ Oxlee argues that smart, bi-directional metering – which measures water delivered as well as received – would transform the monitoring paradigm from being reactive to proactive. ‘It all but eliminates meter reading inaccuracies and can provide near-real time feedback on meter status,’ he says. Data, such as meter readings and fault conditions, is communicated to the back-end application, ‘facilitating accurate billing and proactive management’. He explains that smart, bi-directional systems form a hybrid internet of things (IoT) system, allowing near-real-time interaction with water-management devices. ‘Apps, which leverage the data available, give up-to-date information about consumption and status,’ adds Oxlee. ‘This opens up a new chapter on how consumers monitor and manage their water and is an extended service offering municipalities can offer to their customers.’

These metering systems allow utilities and municipalities to closely monitor water use, while ensuring customers are billed correctly and quickly. ‘There is a dire need for smart metering in the market,’ says Chetan Goshalia, chief sales and marketing officer at South African IoT operator SqwidNet. ‘The benefit of using a smart meter is to get data daily for usage and, building on that, continuous daily reporting in order to start getting trends of usage. Some meters have technology built in that will, through irregular flow, notify someone of that irregularity, which could mean excessive usage or a drop in pressure, meaning something is wrong. Through receiving trends daily, one can pick up an irregularity in that data as well.’ Municipalities as well as the private sector are able to see the daily water usage of their citizens and tenants – and this, says Goshalia, ‘ensures the correct usage is recorded, creating data that is true and correct, ensuring bills are correct, and reducing payment delays, which improves cash flows’.

So how close are Africa’s biggest markets to implementing these kinds of smart water-metering systems? ‘Technologically, we’re already there,’ says Riaan Graham, sub-Saharan African sales director at networking solutions company Ruckus Networks. ‘If you look at today’s IoT tech, there is a plethora of probes that can be introduced into our water-management system to give real-time, accurate data on flow levels, water levels, pressure levels and so on… There are a number of things that can be – and are being – done already. The more important question is: are these technologies actually being embraced, and are they seen as adding value in proactive management of this resource? I don’t think we’re there yet.’

Using South Africa as an example, Graham says that the country’s bigger municipalities are ‘doing a stellar job’ in terms of water monitoring, but adds that there are gaps in that system further up the pipeline. ‘Upstream, where the metros are getting their water supply from, are they making sure the system is proactively monitored? I don’t know,’ he says. ‘Most South African metros have a fairly robust fibre infrastructure, so it would be fairly easy for them to interlink to the probe via WiFi. It’s when you look at the larger picture that it becomes way more complex. ‘The main water supplies from the big dams tend to be in arid areas where there’s almost no infrastructure and the pipes are underground. There you might need to look at public-private partnerships using a combination of WiFi, GSM [mobile data] and fibre to build the network.’

Oxlee, meanwhile, is already looking at smart water-metering systems that will provide real-time monitoring to the user’s smartphone. ‘In order to have those smartphone-based water-monitoring apps, water-management devices need to be connected to a meter-management system – usually via the internet – following an IoT or hybrid IoT model,’ he says. ‘This means the devices need to connect frequently and preferably have bi-directional capability. The building blocks are in place, and Utility Systems has several early adopter pilot sites testing this model. Broader adoption will take several years, but I expect to see fully implemented smart water metering within the next seven to 10 years.’

In the meantime, Africa’s water users and water suppliers will have to keep on checking their meters, continue asking questions about their bills … and persevere in looking for all that missing water.