According to the World Bank, 80% of the main road network in Africa is now in either ‘good’ or ‘fair’ condition, a vast improvement over the past two decades. However, challenges remain: in terms of density of roads and percentage of roads that are paved – the continent still lags behind the rest of the world.

In addition, Africa’s rapidly expanding cities suffer from ever-increasing congestion, which negatively affects economic activity, is a major source of pollution and results in a higher incidence of road accidents. (African roads remain the most accident-prone globally.) Nonetheless, there is something of a road and highway infrastructure boom occurring in the continent’s major cities.

In South Africa, expansive bridge and highway projects are emerging at pace. The country’s current urban landscape displays a variety of pioneering road projects, ranging in scale, ambition and effectiveness. Overall, a great deal of public money is being invested in infrastructural projects. In Gauteng alone, the Department of Roads and Transport invested more than ZAR30 billion between 2014 and 2017 – much of this on upgrading the road networks. A quick tour of South Africa’s primary cities provides a snapshot of where this money is being spent.

On the more architecturally spectacular side, the South African National Roads Agency (Sanral) recently awarded a ZAR1.65 billion tender for a huge new bridge project on the N2 Wild Coast road, with construction due to start in early 2019. The Msikaba bridge will be the second-longest built in Africa, and the third highest. This imposing concrete structure is expected to use nearly 3 000 tons of structural steel and 2 500 tons of cables. This follows the announcement of the ZAR1.63 billion Mtentu bridge – also part of planned improvements to the N2 Wild Coast road – that is scheduled to be completed in 2020/21.

In Durban, there is the Cornubia bridge, a key component of eThekwini’s GO!Durban integrated rapid public transport network. The bridge, 125m long and 50m wide, is composed of three separate smaller bridges that have been bonded together. The structure carries six traffic lanes, pedestrian walkways and two bus lanes.

A less dramatic but pragmatic programme of road improvement is under way in Cape Town. As part of the city’s traffic congestion-relief programme, five significant new roads have been built to relieve traffic since 2015, with another six projects in the pipeline. Over the next three years, more than ZAR480 million has been set aside by the city for traffic-congestion relief projects, including further road construction.

Apart from impressive engineering, what all these projects have in common is that they are not just spectacular displays of concrete and steel, or about getting from A to B in record time. They are about uniting divided cities, creating economic opportunity and accelerating development: in short, creating more livable cities. As Thami Manyathi, head of the eThekwini Transport Authority, says about the Durban bridge project: ‘Areas that have been historically segregated are now being linked. This means better access to opportunities, as well as the potential for economic activities to develop around the transport nodes.’

The Cornubia bridge, he says, ‘is a great reminder that the improvement of public transport is not about infrastructure and roads, but about the connections and links human beings are able to make with people and places’. Gauteng Roads and Transport MEC Ismail Vadi concurs. ‘The injection of funds into transport projects is meant to facilitate improved mobility, allow for social inclusion, stimulate economic growth and enable the development of small and emerging contractors.’

Such large-scale infrastructure projects are also very effective job generators. The N2 Wild Coast road project, it is anticipated, will be a major job creator in an area with notoriously high unemployment – bringing the equivalent of 8 000 full-time jobs to the region over the four- to five-year construction period. All this economic activity has a powerful empowerment role too. In the Gauteng infrastructural programme, for example, 91% of the budget for construction and professional services has gone towards the empowerment of historically disadvantaged individuals, and to employing black firms.

One area where these ambitious projects have not really ventured, however, is the world of ‘smart roads’ – the integration of cutting-edge digital and other futuristic technologies into traditional road engineering. Examples of such innovative – at times speculative – road engineering schemes include solar roadways.In this concept, hard-wearing solar panels replace traditional tar roads, collecting and storing solar energy in photovoltaic cells. This energy can later be distributed to municipal grids, or even to cars traversing the smart roadway. A related idea is photoluminescent road markings, which absorb sunlight during the day and produce illumination at night.

Other innovations include ‘smart concrete’ – where sensors, data-capture capabilities and wireless connections are embedded in concrete panels. A road surface constructed in this way would be responsive to changes in the environment; it might detect the presence of vehicles, track them in real time, and collect data on traffic jams, road conditions and accidents. It could also communicate all this data to drivers, and ‘talk’ to individual vehicles, traffic lights, law enforcement and the IT systems of whole municipalities. Other speculative designs envision small turbines to trap the updraft from passing cars and convert it into energy to power, for example, street lights.

In a water-stressed country such as South Africa, rainwater run-off from hard road surfaces is also a problem crying out for a technological remedy. There are several existing road-surface technologies that address this. Bio-retention systems make use of plants to allow stormwater to soak directly into the earth. These vegetative systems also offer the benefit of naturally cleaning and filtering the stormwater. Permeable pavements are another innovation: these allow stormwater to infiltrate the ground slowly, rather than washing away into concrete drains.

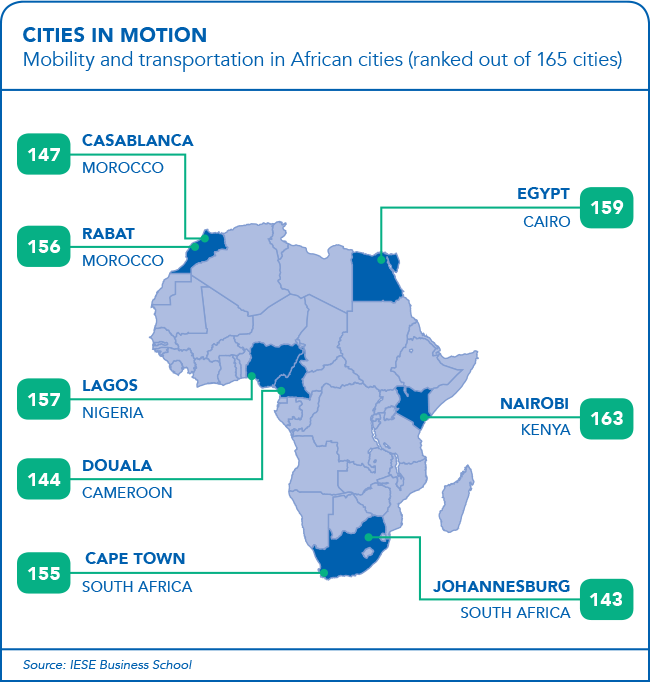

Despite the obvious utility of these technologies in African cities – with their abundance of solar energy, and constant concerns about dwindling water resources – they have not found wide application here. In the University of Navarra Business School’s well-regarded annual table of ‘smart cities’, Cape Town ranks just 143 out of 165 cities – the highest-ranking sub-Saharan country.

The report urges cities to ‘turn to innovation more frequently to improve the efficiency and sustainability of their services’. But there have been only a few experimental African ‘smart’ programmes so far. One high-concept project that has received good press locally is Stellenbosch University’s algorithm-optimised traffic lights – a first on the continent. These are set to be installed in the town of Stellenbosch, in the Western Cape, in early 2019.

Johann Andersen, head of the university’s Stellenbosch Smart Mobility Lab, explains that the project makes use of cameras at intersections, combining this data with information about traffic volume and flow detected by electromagnetic loops already installed beneath the road. ‘This data is then fed into the system, which will automatically adjust the traffic signals to get the traffic moving optimally, based on an algorithm.’

Going by pilot projects in other parts of the world, the scheme promises to dramatically cut travel times and curb traffic congestion. The planned system will initially cover the most problematic section of the busy R44 artery road that runs through the town. Such experimental schemes could be scaled up to meet the needs of the country, and perhaps the continent. It may be that, with the continent’s relatively undeveloped infrastructure and growing need for new construction, African cities might be the perfect showcase for newer, smarter road networks.