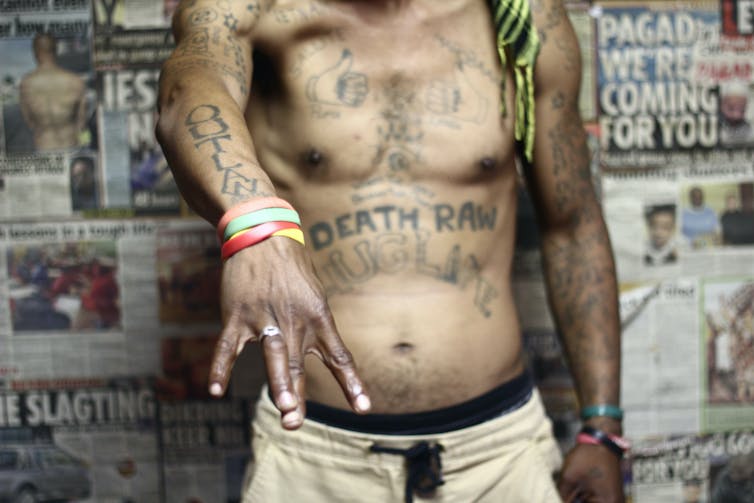

Courtesy Dariusz Dziewanski

Dariusz Dziewanski, University of Cape Town and Robert Henry, University of Saskatchewan

At first glance, it would appear that there’s little in common between the vast plains of the Canadian Prairies and the mountainous swells of South Africa’s southernmost coastline. But take a closer look into cities like Calgary, Winnipeg, and Saskatoon, on one hand, and Cape Town, on the other, and you’ll come across the gangs in each city.

Although they exist in different socioeconomic, historical, and geographic contexts, our recent paper finds that street gangs in Cape Town have key things in common with those in Prairie cities. Both are subcultural groups seeking empowerment and protection in areas defined by structural oppression and exclusion.

As a criminologist with extensive research experience in South Africa and a Métis professor of Indigenous studies in Canada, we’ve both studied how and why individuals become engaged in street gangs in our respective countries of interest.

Researchers often overlook the similarities between street gang involvement and its connection to marginalisation and colonisation in South Africa and Canada. Our paper compared the life histories of 24 gang members from Cape Town to those of 53 members in Prairie cities. Our findings are represented through the accounts of two former gang members, Gavin and Roddy, in South Africa and Canada.

Whether in South Africa, Canada, or elsewhere, gangs are an embedded, systemic feature of unequal and exclusionary urban landscapes. They are often an indication of larger problems in the societies in which they exist. The deep-rooted contours of discrimination, disenfranchisement, and disempowerment – past and present – shape social life in Cape Town and on the Canadian Prairies. They create the conditions in which many young Coloured and Indigenous men and women turn to gangs.

Gavin and Roddy

The paper presented in this article adds to a small but growing body of gang literature that draws comparisons across international contexts.

Gavin, a long-time member of the Mongrels gang, grew up with an abusive father in an impoverished informal settlement on the outskirts of Cape Town. He explained:

There’s no jobs, right. It’s the gangsters here that have the money. They put food on the table … It’s what I was attracted to.

Street cultural gang research suggests that, for those living in tough circumstances, aggression and violence are a sure way to get respect – or “street cred”. Says Gavin:

The reason (gangsters) shoot constantly – that they do it every day – is they want to … make a statement and become famous – put their name out. Then he has the power…

For Roddy, a member of the Native Syndicate in Winnipeg, Manitoba, respect was associated with “acting crazy”:

At the time, being crazy gave you that status and people knew you.

Roddy also spoke about the same challenges Gavin faced, and how being in a gang provided a solution:

No water, no money, no brotherhood … the identity of something (the gang) made you feel important … I felt so awesome when I joined the gang, I felt like: wow your problems are over. I didn’t even know what I was getting into.

Although Gavin and Roddy grew up on different sides of the world, each saw gangs and street culture as a way to gain access to the basic amenities of life where legitimate opportunities were not afforded.

Mapping marginality

Cape Town’s most powerful street gangs are found in communities that are predominantly Cape Coloured – a multiracial ethnic category in South Africa – and often beset by joblessness and violence.

Courtesy Dariusz Dziewanski

In Winnipeg and other Prairie cities, gang membership is dominated by Indigenous youth living in marginalised neighbourhoods that are seen as gang controlled.

Gang membership in each research context has long colonial roots linked to historical struggles of Coloured and Indigenous populations to endure successive state campaigns directed at their cultural erasure through institutionalised violence.

For example, in South Africa, the term “Coloured” was produced through colonial efforts to force people of diverse geographical and cultural origins into a single racial classification. Later, forced relocations under the apartheid regime violently tore apart Coloured communities – as well as other racialised groups – to make space for white-owned real estate in the city centre. This encouraged the formation of gangs that provided adrift youth with a sense of belonging, purpose and empowerment.

Courtesy Robert Henry

Similarly across the Prairies, street gangs have emerged due to the fragmentation of Indigenous families and identities. This occurred first through the Indian residential school policy, which removed children from their families, placing them in state and church run schools. Here they were stripped of their cultures and languages, and many children died. It later also happened through child welfare policies which scooped children away from their families and placed them in non-Indigenous homes. Settler colonial policies such as these have created the social conditions and inequities that enable Indigenous street gangs to emerge and expand.

What this means

Actions taken in the streets can seem random or senseless to the outside observer. But consistently acting “crazy” and seeking violent confrontation expands a gang member’s social and personal esteem by conforming to gang ideals of toughness and fearlessness.

Gang membership was a calculated move that provided Gavin, Roddy, and others in our study with what they believed to be their best chance to survive.

Courtesy Robert Henry

Follow African Insider on Facebook, Twitter and InstagramSource: The Conversation

Picture: Pixabay

For more African news, visit Africaninsider.com

Denied access to legal sources of income and other forms of human capital, marginal populations turn to the streets and to violence. Gang membership helps them construct defiant identities. In the short term street culture gives gang members some hope for empowerment and connections to underground economies.

However, long-term prospects for gang membership are not promising. Most literature on street gangs has shown that involvement is often short-lived and highly violent. Although gang members like Gavin and Roddy do make it out, it’s not easy and can be deadly.

More needs to be done to create equitable and just societies in which young men and women do not feel that the gang is their only choice.![]()

Dariusz Dziewanski, Honorary research affiliate, Centre of Criminology, University of Cape Town and Robert Henry, Assistant professor, Indigenous Studies, University of Saskatchewan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.